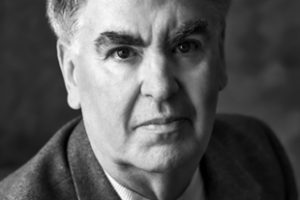

Michael Saltis with the Catholic Business Journal, caught up with author Michael Walsh by phone regarding Walsh’s compelling book, The Fiery Angel: Art, Culture, Sex, Politics and the Struggle for the Soul of the West.

As a journalist, author and screenwriter whose works include six novels, seven works of nonfiction, and the hit Disney movie “Cadet Kelly,” Mr. Walsh delivered an exceptional interview.

Not surprising.

Walsh is also the former classical music critic for Time Magazine, and he regularly contributes to PJ Media, National Review and the New York Post. Michael Walsh’s awards include the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for Distinguished Music Criticism (1979) and the American Books Awards prize for fiction for his gangster novel, And All the Saints (2004).

Following Walsh’s previous hit, The Devil’s Pleasure Palace: The Cult of Critical Theory and the Subversion of the West (2015), his newer book release, The Fiery Angel, is aimed squarely at the connection between the twin crises of the Western world’s artistic and political spheres. The book’s official description sets the tone, as follows:

In Western Civilization, the arts embody the eternal battle between good and evil, and through understanding the arts, we can address the political issues that plague us. Far from being museum pieces, simple recreation, or tales and artifacts from the past, the arts should be seen at the wellspring of our politics, and in particular in public policy debates. They are actually the reason we have public and foreign policy in the first place. In an age that prizes specialization, it’s a mistake to think of public/foreign policy as a discipline onto itself. The Fiery Angel is an historical survey showing significant ways the arts both reflect and affect the course of history, and outlines the way forward, arguing for the restoration of the Heroic Narrative which forms the basis of all Western cultural and religious traditions.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky, in Demons, notes that, ”Man can live without science, he can live without bread, but without beauty, he could no longer live, because there would no longer be anything to do to the world. The whole secret is here, the whole of history is here.” The quote captures something of the essence of Walsh’s book.

And now, the interview:

CBJ (Catholic Business Journal): In addition to being an accomplished screenwriter, novelist, and journalist, you are also the former classical music critic of Time Magazine. In your previous book, The Devil’s Pleasure Palace, you dealt with the impact of cultural Marxism on our collective psyche. It was a hit among readers who feel that the West has lost its way as a Christian civilization. Is your new book, The Fiery Angel, a direct sequel to The Devil’s Pleasure Palace?

MW (Michael Walsh): Yes. In fact, The Fiery Angel takes the ideas that I outlined in the first book and expands them in a more prescriptive way to lead our readers to more works of art. There’s not as much in it about the Frankfurt School [Interviewer’s note: The Frankfurt School is the name associated with a group of intellectuals who fled Germany in WWII and whose Marxist critique of the West was subsequently proliferated in the United States’ educational system]. It was the focus of the first book,The Devil’s Pleasure Palace, but this book—The Fiery Angel—is more positively tilted. I wanted to introduce a lot of great artworks to readers who may have become disassociated from their own culture. When I started this project with Devil, which came out in 2015, Western civilization was not under as blatant an assault as it is today.

The urgency of the second book became clear to me after we saw the reception of Devil. That’s why I’ve written The Fiery Angel, which is also, of course, another opera title. You may get a sneaking suspicion there’ll be some opera in this book, as there was in the first book. And, you’d be right.

CBJ: Historically, art and religious expression in the Christian West have gone more or less hand in hand. The Medieval cathedrals, for example, are filled with paintings and sculptures intended to convey the grand story of Christian civilization to the illiterate. What is the West’s “heroic narrative” that these works of Christian iconography communicated, and how do you tackle this in your book?

MW: I outlined my theory of the heroic narrative in Devil. I’ve extended it in Angel to include works of art that really reflect that. I think it’s characteristic of Western art, and by art, I mean visual art, sculpture, music, drama, poetry and cinema. It’s essential to the Western notion of who we are.

The short version of the heroic narrative is the Jesus Christ story, which is then prefigured or echoed in the myths, legends, fiction, prose and poetry of the West.

That’s really the story.

Disney has made an entire empire out of it, and so did Joseph Campbell. This is not original with me in terms of the “hero’s journey,” but the hero suddenly faces a crisis in his life that he didn’t know was coming. He can choose to embrace it or reject it, and if he rejects it, there’s no movie, there’s no resurrection. The hero in the stories we follow accepts it and undergoes a significant change. At the end, he either triumphs or fails, or triumphs in failure.

I distinguish this from other cultures, which seem to me less focused on the individual and more focused on the group.

Since we’re up against cultural Marxism, which is entirely group-oriented and posits beliefs and commentary that include identity politics as superior to the fate of any individual, the collective over the individual, I think it’s time to re-emphasize what brought the West to its peak of preeminence, and what we stand to lose if we lose our Western culture.

CBJ: In your view, would the crisis in the arts be a manifestation of an overall spiritual crisis in the Christian West?

A: Yes. I made the point in Devil that a lot of this antedates the Christ story. Religion and arts are uniquely symbiotic in a way that, say, science and religion are not. We could get into Aquinas, but this is not the place for that. The arts have always had a kind of incantatory, quasi-liturgical feel to them, and sometimes very explicitly, obviously, with all the sacred music of the Church, Church iconography, et cetera.

My main goal in writing both of these books was to remind especially Americans that the arts are important, that they’re not just entertainment. This is especially true of music because music has been ghettoized for lots of reasons, but mostly because the post-war avant-garde really destroyed the audience’s relationship to tonality and to melody, and to all the things that we think of as being musical. It cut classical music off at the knees.

A lot of people have just decided that classical music is a rich man’s pastime, or it’s “too long,’ or ‘too boring.’ As a graduate of the Eastern School of Music and someone who was involved in the music business as a critic for a total of 25 years, I thought it was time to reintroduce music into its proper place in intellectual history and artistic history.

CBJ: GK Chesterton wrote: “If there is no God, there is no purpose.” In your view, could the decline in the arts in any way be tied to an overall decline of religious practice in Western society?

MW: That’s a good question. I don’t know, I didn’t explicitly link that, but I think you could certainly make that argument that the arts take us out of ourselves in a spiritual way that is not necessarily liturgical.

If you follow the St Matthew Passion of Bach, for example, you find that you’re caught up in the drama of the Passion story, something that Mel Gibson reminded us all of again with his movie several centuries later. But you are also having a religious experience as you listen to it, because if you had listened to it when it was premiered, you would have been in a religious service, participating in it.

Bach established the techniques of musical dramaturgy in a liturgical setting, and then composers were free to take it further than that, and to break it away from the Church, as Mozart did certainly in his operas, and here we are. So yes, the two (God and purpose) are very closely connected.

CBJ: As the official description states, your book is an historical survey showing significant ways that the arts both reflect and affect the course of history. What events do you focus on, and how do you make that connection in your book?

MW: In the first book, I used the twin analytical tools of Milton’s Paradise Lost and Goethe’s Faust: Part One, and related them to a whole interconnecting series of arts and historical developments.

In this book, the primary big poem that I’m talking about is The Aeneid by Virgil, so right away, you connect that to Roman history. Of course, this is the beginning of the West as well. The way that Virgil in the time of Augustus delineated the events, he culled from mythology, many of them drawn from Greek sources, obviously, and the Trojan War, to give the Romans a sense of where they came from and who they were, and to instill national pride as the republic had turned to the empire.

So, there’s one example right there.

If you read The Aeneid thoroughly and closely, you’ll see how much of an effect it had not only on the Romans—who were past Augustus and heading into the decline and fall of the Empire over the next several hundred years, but also on subsequent civilizations, including poets of Renaissance Italy, for example.

Clearly the Divine Comedy, which includes Virgil himself as a character, would be unthinkable without The Aeneid. The same is true for so much of Hollywood and all the great Greek and Roman movies that have come out of it. We’ve watched the cautionary tales of the Roman Empire, thanks to Gibbon, and it’s something that we think about, especially as Americans, because we’re often related to Rome in many specific ways. There’s always a worry about whether this is the end of the “American empire.” Knowing the past helps us know the present, and therefore points us towards the future.

CBJ: Speaking of the present, the West—whether Great Britain, Europe or the United States—has faced several large-scale political crises in recent years. And there is also a general sense that we don’t know who we are or what sort of future we want to work toward, together. Having considered those historical precedents, what political issues are impacted by the crisis in the arts as we are experiencing them today?

MW: I would say the notion of American exceptionalism is one that’s very strong, because when you take away the heroic narrative, when you take away the primacy of the individual—or as I said in the first book, we all want to be the hero of our own movie—when you take that away, you begin to force people into a collective, then you’ve changed the character of America. I do believe this is the goal of the cultural Marxist, to change the character of America.

They were not able to change the character of America economically because Marxism failed, but via the Frankfurt School they certainly introduced a note of self-doubt that is extremely anti-Western and extremely un-American.

We’ve fallen for it [self-doubt] to a great extent, and we see the results of it now all around us, especially in the universities, where terms like “diversity” and “inclusion” have become not simply prescriptive, but they’ve become the only goals of the educational system, which is to force people, again, into thinking of themselves as collections of people with various sexual character or emotional traits or racial traits, and to associate with each other on that basis alone. That really damages American democracy and the whole idea of America.

CBJ: Do you think there is a way for Catholics specifically, but also Westerners generally, to respond to migrants and asylum seekers in the numbers that they’re coming with true compassion, while also taking into account the concerns of domestic residents who are rightfully concerned?

MW: I think every Catholic—and you know, I’m a Catholic obviously—needs to consult his or her own conscience about that. I’m not sure this is something that can be dictated by fiat, whether from St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, or the Vatican or any place else.

Certainly, Christians are demanded to love thy neighbor as themselves, but not at the expense of having their own indigenous culture severely affected. I think that’s a very reasonable worry, which, if you look at what’s happened in Germany, in France and in Belgium, certainly, it gives you pause. This is where we are right now.

CBJ: What is the way forward for the arts that you propose in The Fiery Angel?

MW: The Fiery Angel is not a policy book. It is a book for people to pick up and to learn from. But I can say that it opens with a quote from the beginning of Agamemnon, the first of The Oresteia plays, and concludes with a quote from The Eumenides.

I wanted to bookend The Fiery Angel with the thought that we really haven’t come all that far from the concerns that the Greeks had and from what Sophocles was writing about in The Oresteia, and that our lives should be seen in the overall context of this long and very proud civilized tradition.

I think the thing that the Left has always strived to do, from every millenarian movement since Rousseau, is to create a new man.

As you know, Rousseau was really the sort of beginning of all of the sort of Marxist evil that got unleashed into the world, especially the notion that there could be a new man, or as the Russians used to call him, the “new Soviet man,” who would react and respond to stimuli in ways completely different from how any other human being had ever responded before. I think that’s a very dangerous fallacy, and so what I’ve tried to show is that we really aren’t very much different from the Greeks, and it behooves us to remember where we came from.

CBJ: Saint John Paul II said that “Beauty is a key to the mystery and a call to transcendence. It is an invitation to savor life, and to dream of the future. That is why the beauty of created things can never full satisfy. It stirs that hidden nostalgia for God.” Do you believe that there is a role that the Catholic Church can play in the restoration of the West’s heroic narratives?

MW: St. John Paul II was a man of the theater before his priesthood. He understood the power of the arts in a direct and very vivid way as a young man. I wish the church would be less focused on the issues that it appears to be focused on right now, including social justice. I think that is, again, perhaps more a matter of conscience than it is for church dogma. I don’t see an institutional role, unless the Church were to somehow roll back Vatican II and some of the, I think, wrong paths that we went down, but that’s a debate for Catholics to have.

CBJ: If this book is to have any impact in revivifying the culture, who are the readers you most want to reach, and what do you hope they will take away from it?

MW: I want people who are lacking something in their lives to realize that what they’re lacking is this connection to our artistic and cultural heritage, and to learn to appreciate it, prize it and defend it. That is, in fact, the purpose of both these books.

RELATED RESOURCES:

- The Fiery Angel: Art, Culture, Sex, Politics, and the Struggle for the Soul of the West , by Michael Walsh

- Encounter Books

- And All The Saints, by Michael Walsh

- The Devil’s Pleasure Palace: The Cult of Critical Theory and the Subversion of the West, by Michael Walsh

- Demons, by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

-

Roman Catholicism: The Basics, by Michael Walsh

You must be logged in to post a comment.